Antarctica

January 7, 2017

This winter, I visited the otherworldly Antarctic peninsula. It was an adventure full of cold wind, zodiac boats, and penguin hops.

The idea for the trip came in May, 2015, when I brainstormed on what I wanted to have achieved in the next five years. At the top of the list was to visit all seven continents.

To visit my final two continents, South America and Antarctica, I booked a ticket for this Quark expedition, a 10-day trip aboard the Ocean Endeavour that would sail me across the Drake Passage, from Argentina to Antarctica.

I had a wonderful time! Below are some stories covering moments that I don't want to forget.

Waking up to Rocking

Somewhere over the middle of the Drake Passage, I woke up in the pitch black of a windowless cabin, almost horizontal except for the fact that my head was 30 degrees below my feet. In a few seconds, the boat shifted, rotating the other way until my feet were 30 degrees below my head. A few more seconds, then another rotation.

"Is it supposed to be this bumpy? Should I be scared or calm?" I wondered. Hoping for the best, I went back to sleep and dreamt alongside the rocking.

In a few hours, I woke up to my alarm clock and took a uniquely interesting shower. The fact that I managed to not fall to my face is a deep and inexplicable mystery.

I then went to the dining hall for breakfast, hoping that by the power of the seasickness medicine I'd taken preemptively the day before, I'd be able to eat without problems. Success!

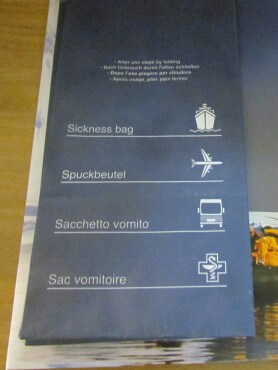

I was fortunate to never need one of the very fancy "sacchettos vomitos" that there were inescapably many of across the ship.

The First Iceberg

"Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. Good morning." Somewhere over the Drake Passage, the loudspeaker of the ship projected the buttery and meditative voice of the bearded, Alaskan expedition leader, Solan Jensen. Solan announced that we might expect to see our first iceberg in the near future, and that there would be a prize for the person on board who spots the first iceberg.

The icebergs in Drake waters generally come from the Weddell Sea, where they've broken off from Antarctic glaciers during summer melting. Their mighty size is incredible, and even more so after considering that most of their mass is underwater.

The first iceberg of the expedition was spotted by a lucky man from California. Believe me when I say I have a lot of photos of this particular iceberg. It was the moment when the trip changed from being somewhere in the middle of the sea to being in the Antarctic realm.

Clean Boots

The ship anchored a few hundred feet away from a site in Antarctica called Brown Bluff, where there are known penguin colonies. The loudspeaker tenderly announced that it was time for my group to "please go to the mud room to prepare for disembarkation".

In the mud room, I put on outerware including a parka, waterproof pants, boots, and a life jacket.

Just before the door to disembark, I stepped into a tray of antimicrobial solution that's designed to keep people's boots from transmitting non-native bits and pieces to the continent. The rest of our outerwear had already been inspected for things like leaf matter in velcro.

After swishing around my boots in the solution, I proceeded to board the zodiac, a small, inflatable motorboat that seats about ten people. The zodiacs were used for cruising and for getting us from the ship to the continent.

Near-Whale Encounters and Struggles with Sea Ice

"Over there!" Someone exclaimed, pointing off in the distance. I looked and saw a dark line emerge for a few moments.

The driver of the boat quietly redirected the motor and sent us that way. The dark specks of humpback whale got larger and larger, and we saw sprays of water as the whale surfaced to breathe.

Soon, we were very close, to the point where the whale tipping over the boat was in the realm of possibility. We floated quietly for a long time, watching the giant mammal at the interface of air and sea. The sight of this mighty beast in the beautiful Antarctic was unlike anything I've ever seen before.

When it was time to return to the big ship, we needed to sail through thick sea ice. It was slow going because the driver had to run the motor low to avoid damaging its propellers in the icy conditions.

All of the sudden, there was a loud popping noise, and the person next to me jumped to the other side of the zodiac as the place where they formerly sat gave way, completely deflating. Sea ice had punctured that compartment of the boat. The driver was unphased and got us back to the big ship safely.

Back on the big ship, we discovered that our driver bears the nickname "Zodiac Killer".

Penguin Curiosity, Dining, and Jumping

On land, I was walking up to where there was allegedly a snow petrel nest. On the way, I needed to cross a "penguin highway", an established path that penguins use for getting from their stone nests to the ocean. We were instructed to stay 15 meters away from any wildlife, but wildlife was not bound by the same rule.

An adelie penguin came up to us and turned his head back and forth, looking at us with one eye and then the other. "He's just checking you out," an expedition guide said. Then the penguin returned to the highway and continued down toward the ocean, where he would swim out to find krill.

As I continued, I saw penguins sitting on nests delicately assembled of sea pebbles. Some were keeping eggs warm, and others were feeding their chicks by regurgitation. The only food source for penguins is ocean life, and chicks can't swim in the cold waters for hunting without their adult feathers, so their parents share what they've caught.

I also noticed the spectacle of penguins jumping back up to their nests. Penguins manage to climb up to great heights by the power of one tiny hop at a time. They can't fly, and they have stumpy little legs that are more helpful for navigating water than land. They've lost the ability to be quick on land during evolutionary history because they have no natural land predators. However, they do need access to land for the purpose of nesting, hence the journey from sea to nest. When they want to jump, they look at the ground, think really hard, and then take the teeniest of jumps. They often fall flat on their faces. Occasionally, I saw one give up entirely on using its legs and instead slide along on its belly. They are adorable to watch.

Polar Plunge

Early on in the trip, someone mentioned the polar plunge, which refers to jumping into Antarctic waters in merely one's bathing suit. I felt a deep, sinking, fearful feeling. I knew it would probably be my only chance to ever do such a thing, but I knew it would be extremely cold and uncomfortable. I wanted to do it, but I also didn't want to, and I was terrified.

As the trip unfolded, I talked to others about it. Some people were dead set on doing it. "I've already come to peace with it," one person said. Others were dead set on not doing it. "I've got a minor heart condition and a major failure of courage," someone said. A couple I met talked about it at length with me. They were on the trip after the lady had survived a near-death experience, and they were doing the plunge. I explained to her that I wanted to do it, but was afraid, and would appreciate any peer pressure she could give me. Her response was a brilliant, "Well, I've got metal in my body, and I'm doing it."

Eventually, I realized that what I feared was not the act itself, but the anxiety of thinking about it so much. I resolved to not think about it and to instead just act, and survive. That's what I did.

I felt happy triumph afterward! I'm glad to have done it. The water temperature was 0.5°C.

"A Good Day in the Blubber Department"

We were sailing in the zodiac and admiring the sides of glaciers until someone pointed out a group of seals on sea ice in the distance. The zodiac driver directed our boat toward them.

We coasted into a tiny channel in between land and sea ice, getting within 20 meters of the beasts. They were halfway sleeping, sitting up every now and then to scratch themselves or check us out with their eyes partially open. "They're like giant cats," our zodiac driver said.

Later in the day, when we were back on the ship and in a lecture about marine mammals by Marla, one of the expedition guides, she said, "Today was a good day in the blubber department!" The exhausted room was mostly silent, with a few woos and some clapping, and she laughed, adding, "Yes, you're allowed to be happy about that!"

Interpretive Dance and Dance Parties

After a final beautiful Antarctic sunset, we began our return journey across the Drake.

A couple of expedition guides were hosting a trivia session in the ship's lecture hall. Participants clumped into small teams and decided on team names. Questions asked included which metaphor Marla had used to describe the appearance of fur seals' teeth and other precise details from lectures. After all the questions, the contest proceeded to the next stage.

The hosts asked a representative from each of the four teams with the highest scores to come up to the front. They announced their team names. "Whale sound", "Quizbergs", and "Poo-nami" ("poo-nami" is a word we'd learned from a video about the importance of whale excrement for krill life in the Antarctic). "We will decide the final winner through an interpretive dance that illustrates your team name," the hosts said to the representatives.

The Quizbergs had a nice, simple dance that illustrated a still, cube-shaped structure that drifts along the sea. "Poo-nami" had a dance that was as amazing as you can possibly imagine it would be, including the representative's pants coming off somewhat. And, last but not least, the Whale Sounds' dance, delivered by a man with a red beard dressed in dark clothing, was a suggestive modern dance that evolved into pole dancing. "Okay, okay, that's enough!" one of the hosts said, and added, "Some things you can't unsee." The audience was rolling in laugher, and one of my teammates turned to me and said, "Some people are extroverted."

The winner, as decided by audience enthusiasm, was the Whale Sounds, and their prize was a round of drinks, which helped fuel the dance party that was coming later in the day.

The dance party began somewhere in the middle of the Drake Passage. A couple of young ladies I'd befriended were so excited because they'd been pushing for the dance party for days after noticing the disco ball in the front of the lecture room. They and other folks populated the dance floor immediately. I was sitting with some new friends close to the bar, talking and enjoying their company for one of the last times before the end of the trip. I'm shy, but I have been known to dance before in public settings, but I didn't think it would happen this time around because there was no compelling enough peer pressure.

The tides turned when the lady from Monaco who I'd seen on the ship but had never talked to took my hand and walked me to the dance floor. I shrugged and waved goodbye to the people I was talking to, and then had a blast alongside the lady from Monaco and others as we danced to pop and hip-hop under the disco ball. Despite the rocking of the ship and the alcohol consumption, nobody fell to the floor dramatically. I certainly needed the exercise after having eaten dessert at least twice a day for the last week. Dancing one's tail off over rocky waters of the Drake Passage is a pretty special experience and a lovely way to wrap up an extraordinarily special trip, full of incredible wildlife, adventures, breathtaking icy scenery, and fascinating new friends from all over the world.